TRY TO DESCRIBE WILLIE NELSON — AND LANGUAGE BREAKS

Try to describe Willie Nelson, and language begins to slip out of your hands. Words circle him, gesture toward him, then fall short. Even Bob Dylan, a man who has bent language to his will for more than half a century, admits the impossible in a recent reflection for The New Yorker: talking about Willie without saying something foolish, inflated, or beside the point is nearly impossible.

Willie is simply too much of everything — and somehow, never too much at all.

How do you define the indefinable? Explain the unfathomable?

Is he an ancient Viking soul wandering the American plains by mistake? A master builder of the impossible, assembling songs out of three chords and a lifetime of listening? Is he the patron poet of people who never quite fit in — and never wanted to? A moonshine philosopher who learned more from back rooms than classrooms? A tumbleweed singer with a doctorate in survival?

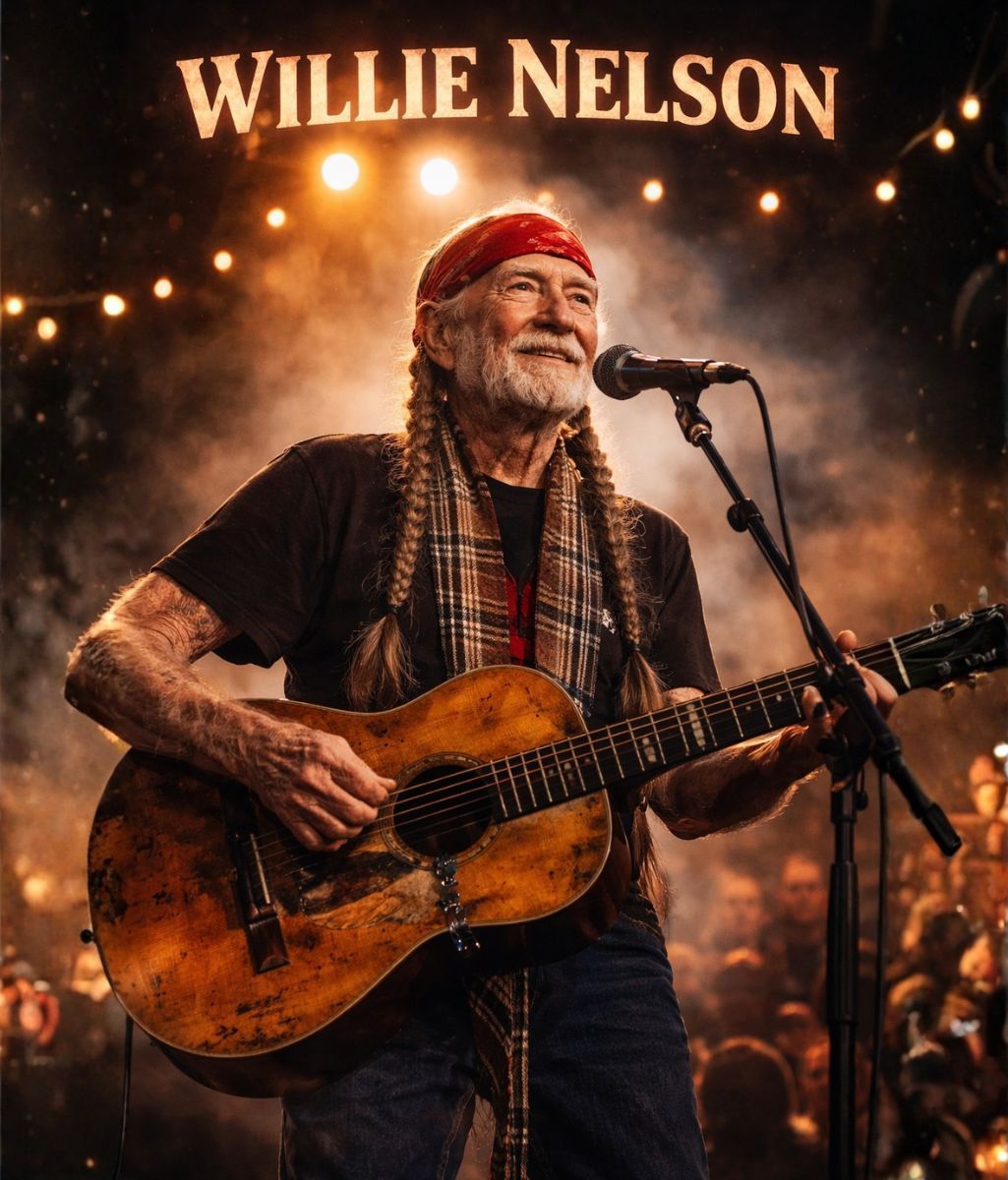

Maybe he’s the red-bandana troubadour whose braids seem to rope eternity itself. Or the man who plays a battered old guitar like it’s the last loyal dog in the universe — scarred, faithful, irreplaceable. That guitar, Trigger, is not an instrument so much as a companion, and Willie doesn’t play it so much as talk to it.

He’s a cowboy apparition who writes songs with holes in them — holes you can crawl through when the world gets too tight. His lyrics don’t trap you; they release you. They offer exits. His voice sounds like a warm porch light left on for wanderers who left too soon or stayed too long. It doesn’t judge which one you were.

You can say all of that — and still not explain Willie.

To Dylan, Willie isn’t a category or a myth. He’s something quieter and rarer: kindness. Generosity. A tolerance for human weakness that never turns into condescension. Dylan calls him a benefactor. A father. A friend. Not just to people he knows, but to people he’s never met — the kind of artist whose very existence makes room for others to breathe easier.

Willie doesn’t loom. He allows.

He feels less like a figure and more like an element. Like invisible air — high and low at once, moving where it’s needed, in harmony with nature rather than in control of it. He doesn’t dominate a room; he settles into it. He doesn’t demand attention; attention finds him.

That’s why he outlasts trends, eras, and definitions. That’s why every attempt to pin him down sounds slightly wrong. Willie Nelson isn’t a symbol to be decoded or a legend to be explained. He’s a presence to be felt.

And maybe that’s the only way to say it without breaking language completely.

He’s Willie.